Exeter Riddle 67

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Mon 02 Oct 2017Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Exeter Riddle 67

Riddle 67’s translation is by Brett Roscoe of The King’s University, Alberta. Thanks for taking on such a tough riddle, Brett!

Ic on þinge gefrægn þeodcyninges

wrætlice wiht, wordgaldra [. . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .] snytt[. . . . .] hio symle deð

fira gehw[. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5 . . . .] wisdome. Wundor me þæt [. . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .] nænne muð hafað.

fet ne [. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . .] welan oft sacað,

cwiþeð cy[. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .] wearð

10 leoda lareow. Forþon nu longe m[.]g

[. . . . . . . . . ] ealdre ece lifgan

missenlice, þenden menn bugað

eorþan sceatas. Ic þæt oft geseah

golde gegierwed, þær guman druncon,

15 since ond seolfre. Secge se þe cunne,

wisfæstra hwylc, hwæt seo wiht sy.

I have heard of a wondrous creature

in the king’s council,(1) magical words [. . .

[. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .] it always does

of men[. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5 . . . . . . .] wisdom. A wonder to me that [. . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .] has no mouth.

No feet [ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .] often contend for wealth,

says [. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .] “(I) have become

10 a teacher of peoples. Therefore now a long time

[. . . . . . . . .]life eternally live,

in various places, while people inhabit

the expanses of the earth.” I have often seen it,

adorned with gold, treasure and silver,

15 where men drank. Let him who knows,

each one who is wise, say what that creature is.

Notes:

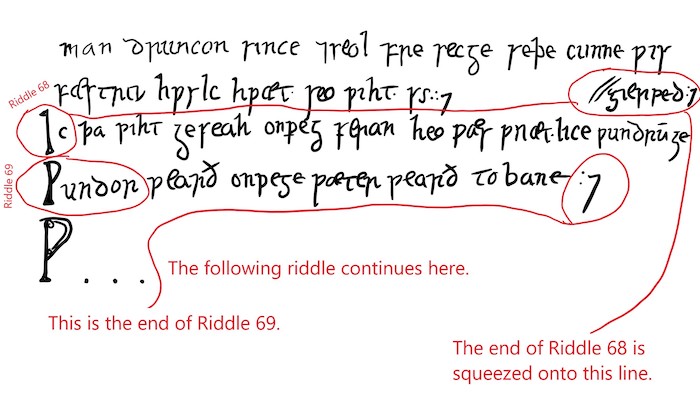

This riddle appears on folio 125v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), page 231.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 65: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), page 106.

Translation Note:

(1) “in the king’s council” can describe either the hearing or the wondrous creature.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 67

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 67

Exeter Riddle 23

Exeter Riddle 60

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 67

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Mon 09 Oct 2017Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 67

Riddle 67's commentary is once again by Brett Roscoe of The King’s University, Alberta. Go, Brett, go!

Let me start by assuring you that this is not a connect-the-dot puzzle, though it looks like one. The rows of periods show where we cannot read the riddle because the manuscript has been damaged. In the Middle Ages, manuscripts weren’t used just used for writing. The manuscript in which most of the Old English riddles are found, the Exeter Book, was used as a coaster, a chopping-board, and later even as kindling for fire! (though to be fair, I should say that this last use was accidental). When you add to that dirt, dust and mould, and natural wear and tear over time, it actually isn’t surprising that the manuscript is damaged. It’s more surprising that it survived, and that we’re fortunate enough to read it today.

That said, though, we’re still faced with the problem of reading this riddle. It may not be a connect-the-dot, but what if it were a fill-in-the-blank exercise? Here is the poem after filling in some of the blanks with suggestions made by various scholars (these are summarized in Krapp and Dobbie, pages 368-9):

Ic on þinge gefrægn þeodcyninges

wrætlice wiht, wordgaldra [sum

secgan mid] snytt[ro, swa] hio symle deð

fira gehw[am. . . . . . . . . . . . . .]

. . . .] wisdome. Wundor me þæt [þuhte

þæt hio mihte swa] nænne muð hafað.

fet ne [folme. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . .] welan oft sacað,

cwiþeð cy[mlice . . . . . . . . .] wearð

leoda lareow. Forþon nu longe m[æ]g

[awa to] ealdre ece lifgan

missenlice, þenden men bugað

eorþan sceatas. Ic þæt oft geseah

golde gegierwed, þær guman druncon,

since ond seolfre. Secge se þe cunne,

wisfæstra hwylc, hwæt seo wiht sy.

O.k., so it’s still not perfect, but we could at least say it’s a bit better. And it can help us flesh out our translation:

I have heard of a wondrous creature

in the king’s council, speaking magical words

with wisdom, as it always does

men[. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . .] wisdom. It seemed a wonder to me that

it could speak as it has no mouth.

No feet or hands[. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .] often contend for wealth,

says fittingly [. . .] “(I) have become

a teacher of peoples. Therefore now for a long time,

always unto life, I can eternally live,

in various places, while people inhabit

the expanses of the earth.” I have often seen it,

adorned with gold, treasure and silver,

where men drank. Let him who knows,

each one who is wise, say what that creature is.

Now the riddle is – though still unclear – legible enough to point to a solution. Most agree that its solution is “Bible,” or some sort of gilded religious book. Lines 5-6 express amazement that this speaker, whoever or whatever it is, is mouth-less. And a mouth-less speaker in Latin and Old English riddles often suggests a kind of writing or writing utensil, since a written text conveys its message to the eyes of the reader without making a sound (see Riddle 60, Riddle 95, and Eusebius’ Latin Enigma 7, De Littera and 33, De Membrano). Besides having no mouth, this strange speaker also has fet ne (no feet), and possibly no hands (if we accept the reconstruction of folme), and it speaks wordgaldra (magical words). Magical words suggest that the book has power outside of its covers; it has authority in the “real” world. It is, after all, a leoda lareow (teacher of peoples). What kind of book would have this kind of authority and power? The Bible, with its message of salvation and world transformation, would seem to fit the bill.

The strongest hint at the religious nature of this book is the fact that it is gilded with gold and silver (lines 13b-15a). Gold and silver were often used to decorate Bible manuscripts. We’ve already seen this kind of decoration in Riddle 26, but just to refresh our memories, here is an example from the Lindisfarne Gospels showing the beginning of the Gospel of Matthew:

This kind of attention was usually reserved for religious texts such as Bibles, psalters, lectionaries, and books of hours. The elaborate decorations reflected the value placed on the content of the manuscript.

So if the answer is a Bible, why are we told that it is often seen þær guman druncon (“where men drank,” line 14b)? If you’re like me, you probably think of reading as a quiet, solitary activity. When I read I make myself a cup of tea, go to a quiet room, and maybe turn on some mellow music. I don’t invite friends over for a party and then pull out a book. Though we may not often think of reading as a public event, it is an activity that provides an opportunity for social bonding. Have you ever been to a public poetry or book reading? Or have you ever read a children’s book to your son or daughter at bedtime? Have you heard the Bible read out loud during a Sunday church service? If so, you’ll have a sense of what this riddle is talking about. In fact, in medieval monasteries it was a common practice to listen to the Bible read out loud during meals. We might say, then, that Riddle 67 uses the kingly hall to represent the monastery. I’m not sure who this comparison would flatter more, the monks or the warriors, but it is not an uncommon comparison in the Exeter Book riddles.

If you’re interested in reading more about early medieval Bibles, you might want to compare this riddle to Riddles 26, 59, and perhaps 95.

References and Suggested Reading:

Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Krapp, George Philip, and Elliott van Kirk Dobbie, eds. The Exeter Book. New York: Columbia University Press, 1936.

Williamson, Craig, ed. The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977.

Tags: anglo saxon riddles old english solutions riddle 67 brett roscoe

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 26

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 59

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 60