Date: Mon 09 Feb 2015

Matching Commentaries:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 35 and the Leiden Riddle

It’s BOGOFF day at The Riddle Ages! For the low, low (free) price of one riddle, you get two related poems! First, take a look at Riddle 35 from the (West Saxon) Exeter Book. Then scroll down to see the Leiden Riddle, a very similar version in another Old English dialect (Northumbrian). Notice any interesting differences?

Original text:Riddle 35

Mec se wæta wong, wundrum freorig,

of his innaþe ærist cende.

Ne wat ic mec beworhtne wulle flysum,

hærum þurh heahcræft, hygeþoncum min.

5 Wundene me ne beoð wefle, ne ic wearp hafu,

ne þurh þreata geþræcu þræd me ne hlimmeð,

ne æt me hrutende hrisil scriþeð,

ne mec ohwonan sceal am cnyssan.

Wyrmas mec ne awæfan wyrda cræftum,

10 þa þe geolo godwebb geatwum frætwað.

Wile mec mon hwæþre seþeah wide ofer eorþan

hatan for hæleþum hyhtlic gewæde.

Saga soðcwidum, searoþoncum gleaw,

wordum wisfæst, hwæt þis gewæde sy.

The Leiden Riddle

Mec se ueta uong, uundrum freorig,

ob his innaðae aerest cæn[.]æ.

Ni uaat ic mec biuorthæ uullan fliusum,

herum ðerh hehcraeft, hygiðonc[…..].

Uundnae me ni biað ueflæ, ni ic uarp hafæ,

5 ni ðerih ðreatun giðraec ðret me hlimmith,

ne me hrutendu hrisil scelfath,

ni mec ouana aam sceal cnyssa.

Uyrmas mec ni auefun uyrdi craeftum,

ða ði geolu godueb geatum fraetuath.

10 Uil mec huethrae suae ðeh uidæ ofaer eorðu

hatan mith heliðum hyhtlic giuæde;

ni anoegun ic me aerigfaerae egsan brogum,

ðeh ði n[…]n siæ niudlicae ob cocrum.

Translation:Riddle 35

The wet plain, wonderfully cold,

first bore me out of its womb.

I know in my mind I was not wrought

of wool from fleeces, with hair through great skill.

5 Wefts are not wound for me, nor do I have a warp,

nor does thread resound in me through the force of blows,

nor does a whirring shuttle glide upon me,

nor must the beater strike me anywhere.

The worms who adorn fine yellow cloth with trappings

10 did not weave me together with the skills of the fates.

Nevertheless widely over the earth

someone will call me a fortunate garment for warriors.

Say with true words, clever with skillful-thoughts,

with very wise words, what this garment might be.

The Leiden Riddle

The wet plain, wonderfully cold,

first bore me out of its womb.

I know in my mind I was not wrought

of wool from fleeces, with hair through great skill.

5 Wefts are not wound for me, nor do I have a warp,

nor does thread resound in me through the force of blows,

nor does a whirring shuttle shake upon me,

nor must the beater strike me anywhere.

The worms who adorn fine yellow cloth with trappings

10 did not weave me together with the skills of fate.

Nevertheless widely over the earth

one will call me a fortunate garment for warriors;

nor do I fear terror from the peril of a flight of arrows,

though they be eagerly pulled from the quiver.

Click to show riddle solution?

Mail-coat (i.e. armour)

Notes: This riddle appears on folios 109r-109v of the Exeter Book and folio 25v of Leiden, Bibliotheek der Rijksuniversiteit, Vossius Lat. 4o 106.

The above Old English text is based on these two editions: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), page 198; and A. H. Smith, ed., Three Northumbrian Poems (London: Methuen, 1933), pages 44/46.

Note that this edition numbers the first text Riddle 33: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 88-9.

Tags:

anglo saxon

exeter book

riddles

old english

solutions

riddle 35

leiden riddle

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 7

Commentary for Exeter Riddles 1-3

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 77

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 33

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Thu 22 Jan 2015Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 33

As with the translation, the commentary for Riddle 33 comes to us from Britt Mize. Take it away, Britt!

When Megan invited me to write a Riddle Ages posting and gave me my pick of Exeter Book riddles, it didn’t take me long to choose. Number 33 has always been my favorite.

The only solution to this riddle that accounts for all the details is “iceberg,” and I agree with those who have thought over the years that the iceberg is colliding with a ship. In other words, I believe that ceol (meaning “ship”) in line 2 is not metaphoric as the Dictionary of Old English assumes in citing this riddle, but a literal ship, and the bordweallas in line 6 are likewise real “walls of board” – here the ship’s hull (although this is also an image from battle poetry, a point I’ll come back to). The iceberg is described as a marvelous, beautiful floating thing, but this one isn’t just floating around beautifully. Although water is beneficial, a fact also referenced in the riddle, as we’ll see, the frozen form that it takes here it is clearly performing an action that is harmful to humans. Otherwise its “laughter,” the noise it makes when it “calls out to shore from the ship,” wouldn’t be, in line 4, egesful on earde (terrible in the land).

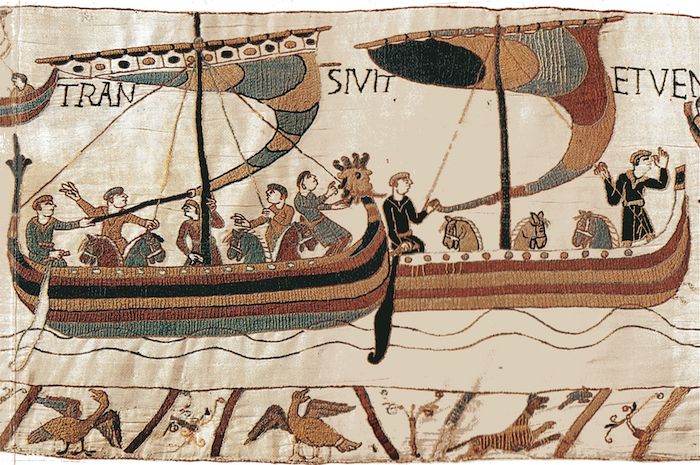

Riddle 33 is a little unusual in focusing on a specific, momentary event. Many of the Exeter Book riddles that have a narrative aspect either recount the object’s creation as a lengthy process, like the transition from animal to detached skin to usable parchment to finished gospel manuscript (Riddle 26), or else they describe habitual, repeated, ordinary actions rather than something that happens once at a certain instant in time (examples of this kind include Riddles 5 and 16). The riddles’ tendency to typify is consistent with their affiliation with wisdom literature – in many cultures the riddle is a wisdom genre – because they are addressing what the world is like, forcing new perspectives or understandings by defamiliarizing the familiar. Even riddles of the “I saw . . .” type, whose narrative setup of witnessing would seem to promise the particular, generally tell of something commonplace and easily or repeatedly observed, like a hand guiding a pen in Riddle 51, or the chicken love that inspires bizarrely ornate poetic stylings in Riddle 42. But while number 33 is a departure from the usual in offering a snapshot of a more singular occurrence and meditating on it poetically, this is not to say that there are no others like it. You might compare the famous Riddle 47, which perhaps has a similar immediacy if we imagine it capturing the moment of discovery that hungry insect larvae have destroyed a precious book, or, outside of the Exeter collection, the riddle carved on the front of a small whalebone box known as the Franks Casket, which narrates the beaching of a whale.

Photo of the Franks Casket (by Michel wal) from the Wikimedia Commons.

Riddle 33 is organized around two different conceits. If you’re a fan of 17th-century metaphysical verse and thus already know what a poetic “conceit” is, you can skip the rest of this paragraph. If you are still reading: a conceit is a metaphor that a poet holds on to through an extended pattern of images and analogies, in order to structure a whole poem according to some non-literal comparison. When John Donne – in a seduction attempt that surely, please, could not possibly work – humorously describes a flea as if it were a marriage bed or bridal chamber, and then will not let go of the idea but just keeps on about it, he has us (and his reluctant lady) in the grips of a conceit.

We don’t normally use the term “conceit” in application to Old English poems, but I’m going to, because it’s a useful angle of approach in this case. So as I was saying, two conceits help to structure Riddle 33 and generate its content. One emerges in a series of details portraying the iceberg as an entity that is not just vocal, but actually linguistic, endowed with the ability to communicate. This is different from the riddles that are in the first person, as if the object were speaking the riddle about itself to us. Rather, this poet as putative observer of a maritime collision describes the iceberg as possessing voice. It “calls out to shore”; even its “laughter” is intelligible, mocking and causing terror to those on land who hear it. The berg’s articulateness is not limited to sound, either. It also writes, when the poet represents the gash it leaves in the broken hull of the ship as a carved character with meaning, a “hate-rune.”

Most interestingly, the “cunning” iceberg “speaks of her own creation” and serves up a riddle-within-a-riddle (a device occasionally found elsewhere, as in Riddle 1’s allusion to the Great Flood, at lines 12-13). The embedded riddle within 33, occupying the last five lines of the poem, is a logic puzzle based on generational paradoxes:

My mother . . . is the one who is my daughter, grown up strong. (lines 9-11)

This intellectual stunt compares loosely with the one in Riddle 46, where familial relationships get tangled up in the kind of arithmetic that only incest can solve. A more exact comparison, albeit from modern times, is William Wordsworth’s famous line “The child is father of the man” (“My Heart Leaps Up”). The poet of Riddle 33 plays the same game of putting something logical into an illogical form of statement, forcing the reader to squint at the truth sideways and see it in an unaccustomed way.

Here the trick applies to elemental rather than human relations. The short, embedded riddle summarizes a northern version of the hydrologic cycle. An iceberg’s mother is water, “grown up strong” into a glacier or icecap, from which the iceberg calves off into the sea. Its daughter is meltwater. After evaporating and falling again, often as the rain that is welcomed in “every single land,” the water “grow[s] up strong” again into ice and glaciers, and around and around we go.

The other conceit in Riddle 33 is, of course, battle. Several details represent the collision as a violent fight in which the adversarial party is, counter-intuitively, slow-moving and also female. Seemingly contradictory notions like being dangerous yet “slow in combat” are around every corner in the Exeter Book riddles; the imagery here is like describing the sea floor as a “wave-covered land” or saying that “homeland is foreign” to a ship’s anchor (both examples from Riddle 5). Old English riddle writers loved these kinds of formulations, and once the solution is found they always turn out to make impeccable sense after all.

The battle conceit is also where the bordweallas I mentioned earlier fit in. In heroic poetry, a row of wooden shields carried by warriors standing side by side is described as a “board-wall.” What the maker of Riddle 33 does here is literalize a term that is expected to be semi-metaphorical. A reader familiar with conventional battle description could chase this word into the wrong frame of reference. Similarly, the ecge (edges) in line 4 are here just edges, but in Old English poetry the word is more often a metonym for “swords” – so often, in fact, that like bordweallas, the literal meaning needed to make sense of the cryptic presentation here might be too obvious to see at first glance. It’s a clever move, exploiting customary poetic language to make a reader think of swords and shields, while leaving the solution hidden in plain sight.

For Old English poets, nature is splendid and God-created, providing abundantly for human needs, but it’s also very, very dangerous. Nature doesn’t care. Death is part of it, at least in the post-Edenic world, and something is eventually going to get every single one of us. Individuals who find themselves isolated from community are painfully subject to the elements, and groups of people are not safe either: natural forces and processes are always, in this literature, potentially antithetical to orderly human enterprise.

This is the context of thought in which Riddle 33 speaks of an encounter between a piece of technology and a natural phenomenon as if it were a battle. Old English poetry shows us strife between animals and their environments; it shows us the vulnerability of individuals in the face of atmospheric and elemental forces; and it shows us conflict between organized human interests (like those that cause a ship to be built and launched) and the disruptive, damaging power of the things around us we can’t control. A sea-surge strands the whale of the Franks Casket. Fire is the “greediest of spirits” (Beowulf and elsewhere). A storm rampages across human habitations and forests too, in a chaos of wind and lightning (Riddle 1). Exiles risk their lives on the frigid sea and are beaten by hail, the coldest of grains (The Seafarer). Winter weather is said to come with hostile intent (The Wanderer), and frost will tear down even the greatest stone buildings in time (The Ruin, The Wanderer). The same water that life requires can also gather into a terrifying and irresistible torrent (Riddle 84) – or, here, freeze rock-hard into an iceberg that strikes a ship, as if in an attack fueled by malice.

An iceberg striking a ship: I’ll bet that at some point, the wreck of the Titanic has flickered through the mind of nearly everyone reading this. Go with me just a few steps down a crooked path.

Photo of the Titanic leaving Southampton in 1912 (by F.G.O. Stuart (1843-1923)) from the Wikimedia Commons.

If you did think of the Titanic and instantly dismissed it as irrelevant to Riddle 33, you were right, of course. The 1912 collision of a ship with an iceberg cannot possibly have anything to do with a poem that had been sitting in the Exeter Book for nearly a millennium by then. Except – the very fact that the Titanic likely came to mind suggests that an awareness of the modern event will lurk within present-day subjective reception of a riddle about an iceberg wrecking a ship. Our history affects the way this little text exists in our world now. Because the Titanic has presence in our consciousness, it has some influence on the kind of life Riddle 33 takes on in twenty-first-century eyes, ears, mouths, and minds.

The Titanic’s demise came as such a shock to the public that even a century later, it’s hard to think of icebergs without also thinking of the mechanical leviathan whose promoters notoriously billed it as “unsinkable.” That wreck gave us the most famous iceberg in history, and it also gave lasting fame to the Titanic: although a ship so grand was big news in its day, few of us might recognize the name now had it not sunk in spectacular fashion, with massive loss of life owing in equal parts to error and hubris.

In this sense, you could even say the iceberg and the Titanic made each other. Neither would be remarkable in the long view of history had they passed silently in the North Atlantic darkness; it’s their catastrophic meeting that immortalized both, providing us with a touchstone for transit disasters, and for icebergs. To put it another way, the materially destructive encounter was equally – from the perspective of historiography and the popular imagination – a creative one, in that it took the ship’s and the iceberg’s simultaneous arrival at one pinpoint on a map to make an event that large numbers of humans would remember and interpret and tell about again and again.

The English poet and novelist Thomas Hardy (1840–1928) understood this. Late in his long life Hardy responded to the improbable intersection of these two objects in the vastness of time and sea, brought about by the inconceivable coincidence of many unconnected events, with his poem “The Convergence of the Twain,” which represents the disaster as an appointment set by divine powers and punctually kept. It’s a spine-tingling piece worth stopping to read if you haven’t. After a few stanzas contemplating the opulence and wealth that lies mouldering on the seabed, where uncomprehending marine creatures gaze on it vacantly, Hardy backtracks to describe the slow formation of the iceberg and the simultaneous, painstaking construction of the huge ship.

In Hardy’s measured verses the two growing hulks become more tightly associated line by line until Titanic and berg both launch, in perfect synchronicity thousands of miles apart, and journey toward their shared destiny:

. . . the Spinner of the Years Said “Now!” And each one hears, And consummation comes, and jars two hemispheres.

To Hardy, the Titanic and the iceberg not only made each other; they were also made for each other, from the very start. Hardy is well known for his dark, ironic outlook, and for him the wreck of the Titanic encapsulates the vanity of human ambition and delusions of permanence.

If you’ve read much Old English poetry, even just some of the often-translated pieces like The Wanderer and The Ruin, you may already see one of the directions I’m heading with this. Writers in this tradition return again and again to the idea that earthly grandeur and human achievement, however impressive they may briefly be, do not last. Ephemerality is a constant theme. In this respect, Hardy’s attitude toward the decaying remains of the greatest moving object devised within his lifetime has much in common with how an Old English poet might have analyzed the same shipwreck (although the earlier poets, unlike Hardy, take earthly impermanence as a cue to seek the embrace of a merciful God).

Hardy’s poem, with its notion that the Titanic and the iceberg were two interlocking parts of a single fated creation, also always brings to my mind the Beowulf poet’s insistent pairing of references to the hero and the dragon at the site of the battle that neither survives, a pattern that gradually accumulates into a tableau of the death of ancient powers. When old king and old dragon meet their fates in one another, each arrives riding a foamy crest of deep time. As Beowulf approaches what he seems to recognize as his last fight, the aged king pauses to retrace for his men, too young to know for themselves, the course of his extraordinary reign; and that poet backtracks like Hardy to the dragon’s centuries-long possession of a treasure placed in the ground by the nameless last survivor of a nameless, long-dead tribe. The rings and swords of that treasure were as useless to the dragon as the Titanic’s china and mirrors to Hardy’s staring fishes, and like the submerged luxury liner, will remain so after Beowulf’s people burn and rebury it in their grief.

Scholars of Thomas Hardy’s life and works will be able to say whether he was familiar with any Old English poetry. It would surprise me if he had not read at least the Beowulf translation by William Morris. But what draws me into these winding associations when I muse on Exeter Book Riddle 33 is the sense of tragedy and irrecoverable loss – laced with a hint of fatalism – with which I, a cultural heir of the Titanic disaster (and of Hardy’s refraction of it through his own art), cannot help but consider icebergs and ships. Whether the riddle’s early audiences would have heard in it the same overtones of cataclysm I somewhat doubt.

Yet the danger and especially the malice ascribed to the iceberg in Riddle 33 feel urgent and universal: too much so to be explained by such a wreck’s resulting property loss or even death, risked by early English seafarers in relatively small numbers. It’s true that no amount of death is small if it belongs to you or someone dear. But I do think scale is key here, perhaps, because this poem is not really about one iceberg and one ship. It’s about the way the world works. If measuring the greatness of a misfortune by its notoriety, shock value, or number of lives lost – as we tend to do – helps us open a back door into that sense of totality that Old English writers might find in the particular, then irrelevance aside, the comparison may reduce a gap of understanding.

The way of the world, in Old English poetry, leads finally to the destruction and decay of everything under the heavens that touches human interests. You may have a good run for a while, but the icebergs are out there waiting. According to the poet of Riddle 33, their beauty and stately movement – and the astonishing fact that they are made of the same water that is “the dearest of maidenkind,” greeted “with joy . . . in every single land” – must not distract from their hardness when “grown up strong” into floating mountains that crush what people make and do.

It all comes back to the board-walls, in which this poem’s battle conceit and its motif of communication brilliantly unite. The image of a hate-rune carved on the ship’s shield/hull is so moving not because we imagine the inscribed character as carrying magic or a nasty message (although those ideas are present), but because we also get the more basic fact that it lets the water in. One meaning of the Old English verb bindan (bind) is to transfix or immobilize – as if miraculously or magically – and I take this to be a salient sense here, when we are told in line 7 that the iceberg “bound” the ship’s hull “with a hate-rune.” The ship will sink; where it is is where it will stay. Like “I now pronounce you man and wife,” this rune as an act of language doesn’t just announce a thing to be true, but causes its truth. When water’s hatred is written by iron-hard water that is both stylus and battering ram, and when it is written on a ship surrounded by this substance that it can’t function without, but which will doom it once the shield-wall is breached, the declaration of hate is itself a weapon with mortal power.

What Thomas Hardy (with his always vexed perspective on the Deity) attributed to some kind of sinister providence, Old English poets put down instead to chaotic, uncontrollable, impersonal forces of the natural world: forces that play havoc with humans’ attempts to organize and manage their surroundings, and which could thus be imagined as figuratively hostile to rational human undertakings. It may seem curious to describe an iceberg as purposeful and inimical, but the choice is quite effective once we realize that Old English nature poetry is really not about nature, but about subjective experience taking place through interactions with nature – and about the necessity of reckoning wisely with our weakness, individually and as a species, against powers bigger than ourselves. Many of the Exeter Book riddles celebrate human artifice and its products; many others ponder with fascination the properties of animals and other parts of the natural world. Number 33 reminds its readers that useful things are also dangerous, and that dangerous things may be magnificent.

If at times we need our own history – with its Titanics and a million other modern ghosts – to hear authenticity in the words chosen by unknown writers long ago as they confronted the wonders and fears of their lives, then so be it. We cannot shed our history in any case, can never stand outside of culture or stop being ourselves. What we can try to do, even knowing that success is always partial, is conduct ever more informed acts of imagination that help us map experiential worlds we will never inhabit. Who’s to say, in learning and teaching, that the path to more sympathetic understanding of the past must never thread across an outcropping anachronism? Let’s just not stop there long, or get too fond of the view.

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 5

Commentary for Exeter Riddles 1-3

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 16

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 26

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 42

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 47

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 46

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 51