Date: Thu 19 Dec 2019

Matching Commentaries:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 88

We have a guest translator for this riddle: the one and only

Denis Ferhatović. Denis is associate professor of English at Connecticut College and an enthusiast when it comes to poetic creativity. He has brought some of this creativity to the below translation, which I hope you enjoy reading as much as I have!

Original text:

Ic weox þær ic s[……………………

……..]ond sumor mi[…………….

……………]me wæs min ti[…..

……………………

5 …]d ic on staðol[………………..

……….]um geong, swa[……….

……………..]seþeana

oft geond [………………..]fgeaf,

ac ic uplong stod, þær ic [………]

10 ond min broþor; begen wæron hearde.

Eard wæs þy weorðra þe wit on stodan,

hyrstum þy hyrra. Ful oft unc holt wrugon,

wudubeama helm wonnum nihtum,

scildon wið scurum; unc gescop meotud.

15 Nu unc mæran twam magas uncre

sculon æfter cuman, eard oðþringan

gingran broþor. Eom ic gumcynnes

anga ofer eorþan; is min agen bæc

wonn ond wundorlic. Ic on wuda stonde

20 bordes on ende. Nis min broþor her,

ac ic sceal broþorleas bordes on ende

staþol weardian, stondan fæste;

ne wat hwær min broþor on wera æhtum

eorþan sceata eardian sceal,

25 se me ær be healfe heah eardade.

Wit wæron gesome sæcce to fremmanne;

næfre uncer awþer his ellen cyðde,

swa wit þære beadwe begen ne onþungan.

Nu mec unsceafta innan slitað,

30 wyrdaþ mec be wombe; ic gewendan ne mæg.

Æt þam spore findeð sped se þe se[…

………..] sawle rædes.

Translation:

I grew where I s[……………………

……..]and summer mi[…………….

……………]me was my ti[…..

……………………

…]d I in the position[………………..

……….]um young, so[……….

……………..] nevertheless,

often throughout [………………..]fgave,

but I stood straight where I [………]

and my brother. We were both hardened.

Our shelter was worthier, adorned more highly,

as the two of us stood on top. The forest always protected us,

on dark nights, its helm of arboreal branches made a shield

against downpours. The Almighty molded us.

Now our kinsmen, our younger brothers

must come after us, and snatch away

our shelter. I am the only human individual

left in the world. My own back is

murky and marvelous. I stand on wood,

on the border of the shield/on the edge of the table/on the margin of the page.(1)

Mi hermano no está aquí.(2)

But I have to guard the position, brotherless

on the border of the shield/on the edge of the table/on the margin of the page.(3)

I must stand unmoved.

No sé dónde mi hermano debe habitar,(4) possessed by men, their property

in what quarter of the world

he who used to shelter high by my side.

We two were one when waging war.

Yet neither could make his valor known

as we were both no good when it came to battle.

Now some degenerates slit my insides,

tear into my abdomen. I cannot escape.

Following these traces finds abundance who […

………..] advantage to the soul.

Click to show riddle solution?

Antler, Inkhorn, Horn, Body and Soul

Notes: This riddle appears on folios 129r-129v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 239-40.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 84: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 116-17.

Translation Notes:

(1) and (3) Please see the commentary for more information regarding this multiple translation.

(2) and (4) Likewise, an explanation of the parts in Spanish, and my reason for their use, can be found in the commentary.

Tags:

anglo saxon

exeter book

riddles

old english

solutions

riddle 88

denis ferhatovic

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 60

Exeter Riddle 72

Exeter Riddle 83

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 78

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Wed 06 Jun 2018Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 78

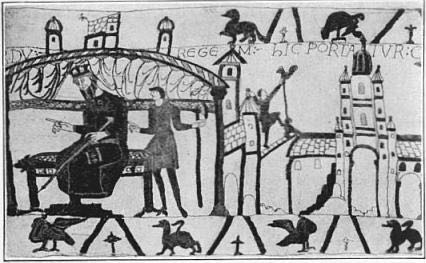

How do you solve a problem like a GIANT HOLE IN A MANUSCRIPT?

The damage to the Exeter Book is so extensive when it comes to Riddle 78 that nearly the entire riddle is wiped out. We have a handful of words at the beginning of the first few lines, and then just nothing at all until nearly the end of the text block. I suppose this means there are lots of exciting opportunities to fill in the gaps? That’s me trying to be an optimist (not my usual thing, so not sure whether it worked!).

Right, well I suppose what we can do is approach this problem from the zero point, and start with a list of things we do know about what’s going on in this riddle. Here we are:

1) There’s a first-person speaker.

2) The speaker can be found under the water, concealed by the waves.

3) The speaker has family or kin.

4) The speaker eats another creature.

5) Either the speaker or its victim travels through the water rather than staying at home.

6) The speaker’s hunting methods are particularly clever.

As in the previous riddle – usually solved as Oyster – there’s an overall focus on water and the concealment that comes from living in such an element, including some rather specific verbal overlap (flod, yþ, (be-)wreon). Even so, this concealment doesn’t protect the speaker’s victim.

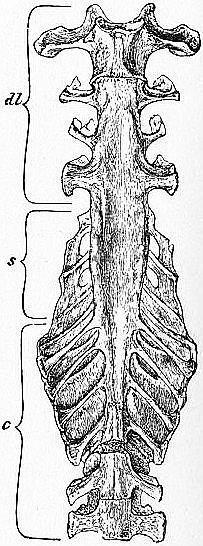

But what sort of animal is the speaker? Reacting to previous scholarship’s lack of interest in this mangled little poem – most folks just wrote it off as yet another Oyster riddle – Craig Williamson argues for Lamprey (pages 357-9). He interprets the clues (well…the ones we can actually read) as referring to a migratory creature with an interesting hunting adaptation. This leads him to suggest the fearsome sea lamprey: jawless, parasitic fish who feed by attaching their suctiony mouths to other fish and then chewing through the scales and flesh with their sharp teeth in circular rows until they can suck their blood.

Wow. You’re not going to sleep tonight, are you?

Williamson’s solution is, however, more than a tad speculative, considering how little of this riddle survives. Much tidier is Mercedes Salvador(-Bello)’s suggestion that the aquatic predator of Riddle 78 may well be preying on an oyster not unlike the one being devoured by a human right before this poem in the manuscript (page 410). The predator and subject of Riddle 78, then, is likely a crab – because crabs were known as the fierce enemies of oysters.

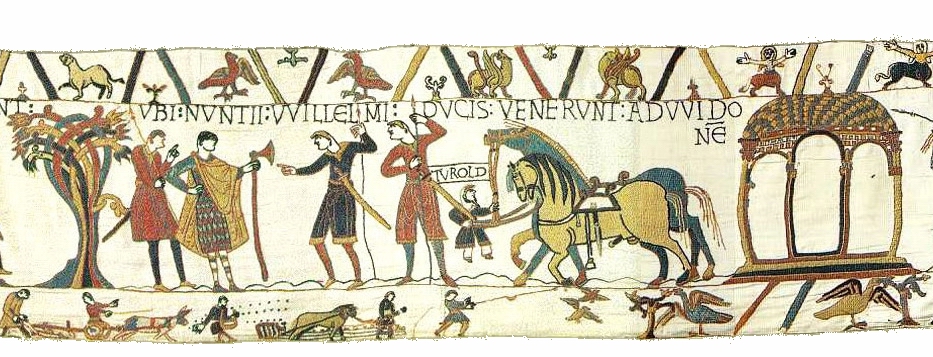

Strangely enough, crabs were reputed to have a particularly clever hunting behaviour: a number of sources from St Ambrose to Isidore of Seville (and beyond!) suggest that they waited for oysters to open their shells and then stuck stones inside to prevent them from closing properly. This enabled them to feast to their little hearts’ delight.

Of course, crabs don’t need to use stones in this way…their pinchers are actually super-efficient:

But this still got me thinking about animal tool use, and I went down the rabbit hole of the internetz to find out more. Interestingly, some types of crab have been observed using tools, even if not – as far as I can tell – in the manner described above (other aquatic animals do use rocks for bashing shells though!). A number of species of crab actually carry plants/algae, shells and rocks, or even deck themselves out with anemones for camouflage and protection (Mann and Patterson). Don’t say I never teach you cool facts.

Crab tool use isn’t just pretty amazing – it also kind of makes you think that late antique and medieval stories about crabs pummeling oysters with stones aren’t really that far-fetched. Unfortunately, we don’t have any of these in Old English, but this may well be what the 7th-century Aldhelm of Malmesbury was getting at in his Latin Enigma 37, Cancer (Crab):

‘Nepa’ mihi nomen ueteres dixere Latini:

Humida spumiferi spatior per litora ponti;

Passibus oceanum retrograda transeo uersis:

Et tamen aethereus per me decoratur Olimpus,

Dum ruber in caelo bisseno sidera scando;

Ostrea quem metuit duris perterrita saxis.

(Glorie, vol. 133, page 421)

(Ancient Romans called my name ‘Nepa’: I stroll along the sodden shores of the foaming sea; I cross the ocean in reverse with turned steps, and yet celestial heaven is embellished by me, when I, rosy, ascend into the sky with twelve stars: the oyster dreads me, frightened by hard stones.)

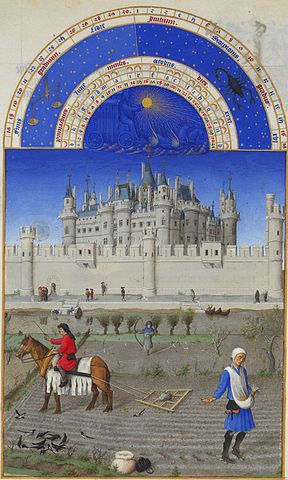

Could this intimidating use of stones be the clever hunting method that the heavily damaged Riddle 78 was referring to? That’s certainly what Salvador(-Bello) reckons! She suggests that the audience of the Exeter Book riddles would likely have known about the oyster and crab’s association, and that they may have even interpreted the two allegorically. They clearly did so for oysters (see Riddle 77’s commentary), and we have early theological texts that suggest crabs were up for grabs, allegorically-speaking, as well. Here’s an excerpt from St Ambrose’s fourth-century Hexameron:

Sunt ergo homines, qui cancri usu in alienae usum circumscriptionis irrepant, et infirmitatem propriae virtutis astu quodam suffulciant, fratri dolum nectant, et alterius pascantur aerumna. Tu autem propriis esto contentus, et aliena te damna non pascant. Bonus cibus est simplicitas innocentiae. (book 5, chapter 8, number 22; Patrologia Latina sections 216A–216B)

(Now, there are people who, like crabs, skillfully creep into the trust of other people, and bolster the weakness of their own virtue by a certain cunning; they bind deceit to their brother, and feed on another’s hardship. Conversely, be content with what is your own, and do not feed on others’ misfortunes. An honest meal is the simplicity of innocence.)

This truly fabulous allegory leads Salvador(-Bello) to suggest that Riddles 77 and 78 make a very tidy thematic and moralistic pairing: innocent and defenseless oyster vs voracious crab.

We all know who wins in real life.

References and Suggested Reading

St Ambrose. Hexaemeron. Patrologia Latina Database. Vol. 14.

Glorie, F., ed. Variae Collectiones Aenigmatum Merovingicae Aetatis. Corpus Christianorum Series Latina, vol. 133-133A. Turnhout: Brepols, 1968.

Mann, Janet, and Eric M. Patterson. “Tool Use by Aquatic Animals,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, volume 368 (2013), online here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4027413/

Salvador(-Bello), Mercedes. “The Oyster and the Crab: A Riddle Duo (nos. 77 and 78) in the Exeter Book.” Modern Philology, vol. 101, issue 3 (Feb. 2004), pages 400-19.

Williamson, Craig, ed. The Old English Riddles of The Exeter Book. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 78 latin

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 77