Exeter Riddle 9

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Sun 16 Jun 2013Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Exeter Riddle 9

This week’s translation is a guest post from the very clever Jennifer Neville. Jennifer is a Reader in Early Medieval Literature at Royal Holloway University of London where she is currently working on a book about the Old English riddles. Stay tuned for her commentary in the next post.

Mec on þissum dagum deadne ofgeafun

fæder on modor; ne wæs me feorh þa gen,

ealdor in innan. Þa mec an ongon,

welhold mege, wedum þeccan,

5 heold ond freoþode, hleosceorpe wrah

swa arlice swa hire agen bearn,

oþþæt ic under sceate, swa min gesceapu wæron,

ungesibbum wearð eacen gæste.

Mec seo friþe mæg fedde siþþan,

10 oþþæt ic aweox, widdor meahte

siþas asettan. Heo hæfde swæsra þy læs

suna ond dohtra, þy heo swa dyde.

In these days my father and mother

gave me up for dead. There was no spirit in me yet

and no life within. Then someone began

to cover me with clothing;

5 a very loyal kinswoman protected and cherished me,

and she wrapped me with a protective garment,

just as generously as for her own children,

until under that covering, in accordance with my nature,

I was endowed with life amongst those unrelated to me.

10 The protective lady then fed me

until I grew up and could set out on wider journeys.

She had fewer dear sons and daughters because she did so.

Notes:

This riddle appears on folios 103r-103v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), page 185.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 7: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 72-3.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 9 jennifer neville

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddles 1-3

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 77

Exeter Riddle 42

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 8

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Thu 14 Feb 2013Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 8

Who knew that early medieval England had such a vibrant nightlife? Whenever I read this poem, I’m struck with the image of lounge lizard monks clubbing and singing karaoke (thanks to Elaine Treharne for tweeting this suggestion!). It’s actually rather distracting when it comes to writing the commentary.

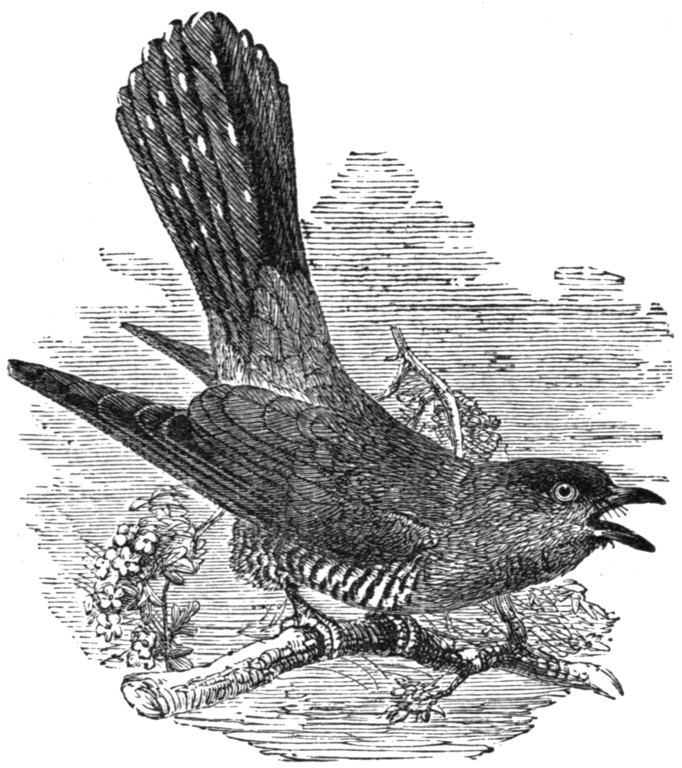

But since you’re no doubt dying to hear more about this riddle, let’s start with the solution. Well, like all of the Exeter Book riddles, this one has had a variety of proposed solutions. According to Fry’s list of riddle solutions (which you really should be getting familiar with by now, but I’ll give you the reference below anyway!), scholars have argued for: Nightingale, Pipe, Woodpigeon, Bell, Jay, Chough, Jackdaw, Thrush, Starling, Crying Baby, Frogs, Soul and Devil as Buffoon. I’ve missed out Flute, but I’m too far away from a library at the minute to check that this suggestion came early enough for Fry to include it in his list. Homework: someone go check this and let us know! But at any rate the solutions are mainly a lot of birds and a few other noisy things. Obviously, sound is the motif we want to tune into (pardon the pun), considering the sheer volume of song/speech words repeated throughout this poem.

But we’ll get to that in a moment. For now, solution-wise, I’m going to throw my lot in with Nightingale, or Old English, Nihtegale. Why?, you might ask, and the reason to that question would be what Dieter Bitterli has dubbed the “etymological principle.” The riddle makes it very clear that what we’re dealing with here is something that sings (galan) in the night (niht). So that would be a night- (niht) singer (gale). A niht-gale. Nihtegale. Got it?

This photo (by J. Dietrich) is from Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Another thing to point out is that our previous riddle dealt with the mute swan. Now we’ve got the noisy nightingale and (spoiler alert!) we’ll continue on with a few more birds in the riddles immediately following. These runs of connected riddles are found throughout the Exeter Book collection, as we saw with Riddles 1-3, and I think they’re very useful in narrowing down the general subject matter of a lot of the poems.

As for the sorts of words this riddle makes use of, we have the ever-popular sound/voice range: reord, heafodwoþ, hleoþor, stefn and woþ. Noise-making verbs include: sprecan, singan, wrixlan (sort of), cirman, styrman, onhyrian and bodian. Then, of course, we have the muþ (mouth) and two references to hlude (loudly), etc. etc. which is all contrasted to the stillness of human-life (stille on wicum / sittað nigende).

But human-life is also present very much in the personification of the birds, which tends to take on some fairly off-the-wall diction from time to time. For example, we’ve got heafodwoþe (literally, “head-voice”), a compound word that is only found here and whose elements collocate (that is, appear close together) nowhere else in the Old English corpus. Both parts of the compound are common, although woþ is especially mentioned along with other “voice,” “mouth” and “speech” words in poems about animals, such as The Phoenix (lines 127-8, 547-8), The Panther (lines 42-4) and The Whale (line 2), or animalistic and demonic forces in Guthlac A and B (lines 263-5, 390-3, 898-900).

Another unique compound is æfensceop (evening-singer), which is basically a way of talking around the riddle’s solution: evening/night + a word for a singer = nihtegale, as above. Scirenige is, perhaps, more exciting because it may be an actress-word. Editors frequently emend it (that is, take an educated guess at a correction) to the form scericge, which describes the entertaining St. Pelagia elsewhere in Old English (see Bosworth and Toller). Unfortunately for my dream of becoming an early medieval actress, though, Mercedes Salvador(-Bello) makes a good case for understanding this word not in terms of acting, but as a reference to light and to the Latin form for nightingale, luscinia. Finally, sceawendwis appears to be linked to entertainers as well, gesturing to a sort of jester-type of silliness: elsewhere, we find the compound sceawendspræc, which glosses the Latin scurrilitas (buffoonery). Bosworth and Toller’s dictionary defines this second Old English compound as “the speech of the theatre.” Although, of course, “theatre” may be slightly anachronistic for an early medieval context.

But there’s certainly something theatrical going on here in the bird-community that may or may not be a bit annoying to those quiet city-folk.

References and Suggested Reading:

Bitterli, Dieter. Say What I Am Called: the Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book and the Anglo-Latin Riddle Tradition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

Bosworth, Joseph, and T. Northcote Toller. An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1898). Digital edition (Prague: Faculty of Arts, Charles University, 2010): http://bosworth.ff.cuni.cz/.

Fry, Donald K. “Exeter Book Riddle Solutions.” Old English Newsletter, vol. 15, (1981), pages 22-33.

Salvador(-Bello), Mercedes. “The Evening Singer of Riddle 8 (K-D).” Selim, vol. 9 (1999), pages 57-68 (esp. 61-3).

Tags: riddle 8 anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 8